Back on July 12, Michael Powell wrote a nice tribute piece to Sarris’ longevity, and provided a well-timed primer for those of us who have wondered where to start when it comes to Sarris’ writings and thoughts. “A Survivor of Film Criticism’s Heroic Age” includes the perspective of Sarris himself on his career, and his career-defining battles, chiefly with Pauline Kael. “We all said some stupid things, but film seemed to matter so much,” he says. It still does, but as Sarris says, the battles reached a fever pitch back in the 1960s. The article provides more details.

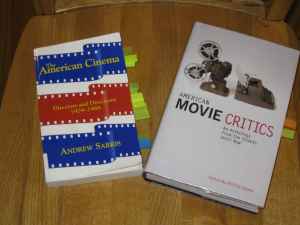

Sarris and Lopate, marked with sticky notes

It’s worth noting that American film criticism didn’t, of course, start with Sarris. That’s why I’m delving into Phillip Lopate’s wonderful collection, “American Film Critics: From the Silents Until Now,” while simultaneously venturing into Sarris’ “The American Cinema.” I picked up both books from the library, and marked them as I read (see picture), but I’ve subsequently ordered my own copy of “The American Cinema.” The Lopate collection is a keeper, too, once I can scrape the funds together (and other priorities aren’t pressing—although they always do press).

So what was I to make of Sarris when he writes, in his chapter on John Ford: “The Left has always been puritanical, but never more so than in thirties when Hollywood’s boy-girl theology threatened to paralyze the class struggle.”

Or later, when he writes, “Ford can never become fashionable again for the rigid ideological critics of the Left.”

Or later still, In his chapter on D.W. Griffith, where Sarris writes about how D.W. Griffith is treated as an anachronism by “the liberal, technological, or Marxist historians who have embraced a theory of Progress in contradistinction to all other arts.”

I found Sarris’ comments unexpected in their general agreement with what might be today’s “conservative” view of Ford and Griffith. I imagine conservatives would nod their heads as Sarris attacks “the Left.” But I imagined Sarris would be mortified to hear me say as much. How had these definitions changed since Sarris wrote?

I guessed that at the time Sarris wrote “The American Cinema” (published in 1969, a year before I was born), there may have been intramural battles among those who were left of center, and that Sarris was therefore engaging in a debate among those who were on his side of the political aisle. Similar to the skepticism with which self-labeled “progressives” viewed other, DLC-type Democrats during the Clinton/Obama primary battles, maybe Sarris had a bone to pick with people to his left.

Or maybe, just maybe, he was a Republican.

Such a label is no scandal to me. I consider myself right-of-center—something that has put distance between me and other film lovers. But more on my politics in a future post.

I put the question about Sarris to two men whose insight into Sarris far exceeds my own: Stephen Prince, film professor at Virginia Tech (my alma mater) and author of several books on film; and Gerald Peary, director of “For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism.”

And then I sent the question to Sarris himself. It was a long shot.

He got back to me through Molly Haskell, his wife and fellow film critic. Read on for the details.

First, here’s Prince, who didn’t mince words in laying out the playing field, and Sarris’ place on it. “To a large extent, Sarris is setting up straw figures (that he calls ‘The Left’) so he can knock them down,” Prince told me. ”He’d have three points of reference when writing in the late’60s and 1970s—the old American left of the 1930s (New Dealers, anti-fascists, trade unionists, communists), the New Left that coalesced around Civil Rights and the Vietnam War, and the intellectual left as embodied in ’70s-era film theory/criticism and select filmmakers like Godard. Seeing himself as not an ideologue, Sarris disassociates himself from all these by taking the critical positions in the remarks you excerpted. I think he comes off sounding rather silly.”

Peary, whose film highlights the Sarris/Kael spats of several decades ago, referenced Sarris’ political philosophy as expounded in “For the Love of Movies.”

“There’s a little bit in my film in which Sarris explains how he and Kael were both ‘centrists’ politically,” Peary told me. “Sarris came from a working-class Greek family in Queens, and, coming into the city, he became a moderate liberal, quite a stretch from his background. But, in his view, the Village Voice in the late ’60s was filled with rich, spoiled, bratty, trust-fund babies who considered themselves holier-than-thou radicals and looked down on his views. And Molly Haskell was seen by some as a “bourgeois feminist” (that was the term), who didn’t connect middle-class women’s issues with the oppression of blacks, working-class, etc. It was a very incendiary time, and they both were bitter about it, a bit paranoid.”

Peary, who lived through that time, told me he considered himself “a leftish agitator” in those days. “The ‘Left’ of the ’60s was more visionary, cultural revolutionist , sex-drugs-rock’n’roll, far more socialist-anarchist than Communist,” he explained.

Having heard from Prince and Peary, and of Sarris’ own explanation of his background in “For the Love of Movies,” I sent the question to Sarris himself, hoping for confirmation or clarification of his politics. Who better to ask?

Haskell responded for Sarris, who had no access to a computer but communicated his thoughts to his wife. She told me that I was on to something in my distinction between factions among the Left, but that the issue was “complicated.” “He was brought up (parents Greek monarchists) on the right, then moved to the center. Most of the time battling far left critics,” Haskell wrote.

But Sarris “has become more liberal since college,” she wrote. “Best description: a liberal anti-communist.”

She concluded, “The Nouvelle Vague was considered apolitical, or even rght-wing by left critics. Godard considered almost a fascist before he was radicalized.”

There’s obviously much more to the story—more than I can figure out now. But Sarris has left a line of communication open to me, if and when I feel competent enough to follow up with him.

It was a thrill to hear from Sarris himself, as well as from Prince and Peary. I’m honored that they participated in this budding blog, and look forward to building on what they’ve told me as I pursue this project.

August 14, 2009 at 6:51 pm |

Although I find both Sarris and Kael’s slamming of liberals to be overwrought at times, you have to remember also they were reacting to the idea at the time of liberal message movies being the best type of movies because they were “good for you.” The idea of expressing any kind of political statement through a genre film would have been anathema to those critics at the time, especially from someone like Ford, who had fallen out of fashion because Westerns weren’t to be taken seriously, and Ford admittedly had turned reactionary in his later years, both politically and aesthetically.